I was asked to share the following mashup of an essay titled “The Endurance of the Color Line” published in the journal Othering & Belonging: Expanding the Circle of Human Concern and remarks I gave as part of a public talk called “Hearts Open, Fists Up” at Central Washington University in Ellensburg, WA. I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

Good afternoon. How are you? Maybe it’s better to ask, are you struggling well?

This is a time of deep uncertainty, of questioning assumptions. But in many ways, it has always been that time, hasn’t it? Who were the first Muslims in America? How did whiteness come to be seen as a legitimate identity? Trump v. the West Coast – how did that happen? The red-blue county map – how did that happen? What does democracy mean, and what does it demand of us? Is democracy something the state does for us, or are we involved somehow?

Why do things happen the way they do? It has always been a time for asking these questions and so much more. If we are not curious about them, then we’re in trouble, because it means we’ve given up on our agency. And by now we should know that no one is coming to save us.

QUESTION EVERYTHING

I was born in a suburb of Buffalo in 1969. My parents were immigrants from Korea, which had just been through a devastating war that is often called “The Forgotten War” because no one really talked about it. Unlike the American War in Vietnam, which was at least at some point televised, most Americans were unaware of its devastation.

My parents were among the first Koreans in Buffalo. My mother started the first Korean church there. Later, when I was about seven years old, she divorced my father. I will always be grateful that she did, but the Korean community, organized through the church that my mother built, kicked her and me out. She walked out of her marriage with the shirt on her back, with me in tow. We moved six or seven times in a couple of years. My Korean friends weren’t allowed to be friends with me anymore, so both my mother and I were thrust into a world of suburban whiteness with no co-ethnic refuge. I learned at an early age, as so many people do, that breaking gender rules has material consequences. Such experiences led me to become a comfortable outlier, because I also learned not to expect to be accepted, to be liked, to be seen as “normal” even (especially?) by my co-ethnics. In hindsight, this was a gift that led me to question many commonly accepted things, and to be better equipped to navigate the world because of that.

I tell you this because “normal” is way overrated. More than that, while “normal” promises safety, it is in fact violent and dangerous. I think that’s the main point I want to make today. We need to have our hearts open and our fists up because nothing we were taught to believe is normal really is. That’s becoming clear. There is no one way to be, to live, or to love, because each of us contains contradictions, and capacities both to nurture and to do harm. To paraphrase Walt Whitman, we contain multitudes. Navigating that reality requires compassion and courage, especially because the systems that shape our lives force us into competition with one another, rather than to be curious about each other.

We just marked the anniversary of Sa-I-Gu, or the Los Angeles rebellion of 1992. I think it’s an opportunity to think critically about where we’ve been and where we are heading. It’s an opportunity to think about norms that divide us and prevent us from seeing where we might have common interests.

For those who might be unfamiliar with the LA rebellion, 26 years ago, in October 1991, Korean American storeowner Soon-Ja Du was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter for shooting and killing a 15-year-old African American girl named Latasha Harlins earlier that year. Du had suspected Harlins of shoplifting, and engaged in a physical struggle with her inside Empire Liquor store in South Los Angeles. When Harlins angrily left her juice on the counter and turned to leave, holding the $2 that would have paid for her purchase, Du shot her in the back of the head. For taking Harlins’ life, Du paid $500 and served no prison time.

Two weeks before Harlins’ death, four LAPD officers were caught on video brutally beating an African American motorist named Rodney King. When the officers were acquitted that following spring, Los Angeles erupted in “civil unrest”. The Los Angeles riots, as the five-day event came to be known, involved 10,000 federal troops, resulted in more than 50 deaths and some 12,000 arrests, overwhelmingly of Black and Brown people. It also caused $1 billion in damages, about half of which were borne by Korean-owned businesses. Korean Americans dubbed the riots, which began on April 29, 1992, “Sa-I-Gu” (meaning 4-2-9, or April 29).

These events were often (always?) narrated in terms of Black-Korean conflict. But it’s not the inherent nature of Koreans to kill or mistreat Black people. It is not the inherent nature of Black people to rebel. We need to ask ourselves why these events happened, what were the conditions surrounding them, and what were the forces creating those conditions. What were the ideas animating them and what purpose do they serve?

THINK STRUCTURALLY & GLOBALLY

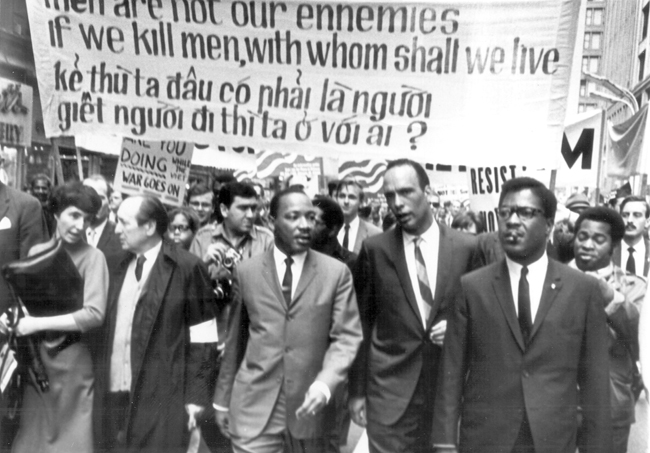

Twenty-five years before Sa-I-Gu, Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his 1967 Beyond Vietnam speech at Riverside Church. In this speech, King knowingly risked alienating significant portions of his base and white liberal powerbrokers by denouncing not just domestic racism, but also militarism and capitalism. He warned that these “giant triplets” formed a blueprint for “violent co-annihilation” and called for a spiritual revolution of values fueled by a deep and all-embracing love. Speaking of the war he said:

Twenty-five years before Sa-I-Gu, Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his 1967 Beyond Vietnam speech at Riverside Church. In this speech, King knowingly risked alienating significant portions of his base and white liberal powerbrokers by denouncing not just domestic racism, but also militarism and capitalism. He warned that these “giant triplets” formed a blueprint for “violent co-annihilation” and called for a spiritual revolution of values fueled by a deep and all-embracing love. Speaking of the war he said:

And so we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. And so we watch them in brutal solidarity burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago. I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor.

The year of Dr. King’s Beyond Vietnam speech there were 159 race riots across the United States driven by the same forces that drove Sa-I-Gu in 1992, and the same forces that drive Black uprisings today: poverty, police violence, political neglect. Among the most devastating riots in 1967 took place in Detroit, a city that now, 50 years later, is under emergency management.

Dr. King’s point about Black and white soldiers killing and dying together even though they couldn’t live on the same block in Chicago, reminds me of something a friend of mine, Felix Sitthivong, said recently:

Throughout my life and incarceration I was always a young and stubborn person. Sometimes I still can be. I used to claim that I loved my neighborhood and that I would die or even kill for the few square blocks that I thought belonged to my set. How ignorant does that sound? How egotistical and narcissistic does one have to be in order to feel as though they have the right to die and put their family through all the grief, let alone take another life, for a few square blocks that we could barely afford to rent on?

Own? Who truly owns a neighborhood? I’ve learned that nobody can ever own a neighborhood. It belongs to the people, and the people are the community. To genuinely say you love your neighborhood is to genuinely love your people and your neighbors. For the longest time, I never understood or even took the time to comprehend that concept. I now reminisce and am ashamed that I was what was wrong with the neighborhood that I thought I loved so dearly. My heart hurts and there’s always a sense of regret when I look back at the person I used to be, and realize that the negative ways that I treated other people was just an internalized emotion that I felt towards myself. So much so that the victim in my case was a young man just like me… who grew up just like me… who had dreams and a family just like me… whose life got cut short because of ignorance and violence… just like me.

Felix is currently serving what is effectively a life sentence at the Clallam Bay Correctional Center, where he is the president of the Asian Pacific Islander Cultural Awareness Group. He grew up as a refugee of the very war that King risked his life to denounce 50 years ago, in a poor neighborhood here in Washington State where gangs became a form of protection. The contradictions that King named endure.

The Beyond Vietnam speech is a careful and powerful call for an internationalist working class and poor people’s unity, and for a feminist politics of non-subjugation, of anti-domination, of radical love. That King was killed exactly one year later has always haunted me. It is as if silencing his radicalism, his unwavering commitment to human solidarity, was necessary for the ruling class to declare the freedom dreams of Black Americans achieved, to erase all arguments for dismantling the color line by denying its existence, by creating new stories about the deserving versus the undeserving of humanity through criminalization and immigration policy.

We could talk about many anniversaries and their meaning today:

- Thirty-five years after the murder of Vincent Chin by two unemployed white autoworkers in Detroit, today’s white vigilante violence targets Muslims, Arabs, Sikhs, and South Asians, as well as Jews, Blacks, and other perceived enemies of white workers.

- Sixty years since the Little Rock Nine integrated public schools in Arkansas, communities are now fighting to keep public schools open. At the same time, that state is rushing the executions of death row inmates before it runs out of the lethal sedative midazolam in what scholar Jelani Cobb has called “the banal horror” of “a lethal clearance sale”. Publicly funded death, but not education.

- We could talk about the Korean War – that forgotten war which never ended, although an armistice was signed over 60 years ago. The United States created the world’s most militarized border at the 38th parallel, which is now the cause of North Korean and U.S. brinksmanship and a nuclear crisis.

These anniversaries are opportunities to look at the conditions surrounding these flashpoints and the responses to them that have shaped American race consciousness and politics. But, how many flashpoints must take place before we acknowledge that crisis is America’s normal?

Today we have no shortage of crisis, no shortage of flashpoints. President Trump dropped the “mother of all bombs” in Afghanistan and is flirting dangerously with nuclear war on the Korean peninsula. Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ has declared an all-out war on immigrants and a revival of the war on drugs, saying, chillingly: “Be forewarned. This is a new era. This is the Trump era.” We have a climate denier and fossil fuel champion in control of the Environmental Protection Agency. People like Exxon CEO Rex Tillerson and Tea Party darling Nikki Haley are setting foreign policy and are the faces of the United States on the global stage. President Trump recently signed legislation aimed at eliminating federal funding for abortion care. Secretary of Education Betsy Devos is eviscerating public education under the banner of “freedom of choice.” And the House Republican majority has voted to eliminate health insurance for the most vulnerable Americans.

It is hard to keep up with the pace of crisis. Internationally the world is burning, literally, with extreme weather events and disasters due to the warming of the planet, causing particular suffering in the Global South and jeopardizing all of us. And Syria. I have no words for the horrifying crimes of the Assad regime against the democratic aspirations of the Syrian people. I fear that the left in the west has profoundly betrayed humanity in its failure to support the Syrian democratic revolution. I also fear the future that the rise of these strong-man regimes globally signal – Putin, Assad, Trump, Duterte, Erdogan, all backed by state power.

And yet there is hope. Perhaps more than at any other time in my life, there are opportunities to shift mass culture, at the very least to popularize and normalize a more critical consciousness. It’s not as if brutal immigration enforcement wasn’t taking place 20 years ago, or that the war on drugs is something new. But now more people are paying attention, wanting to do something, seeing themselves as agents of change.

But what do we, as critically thinking, justice minded thinkers and doers, want? What will lead us out of this, what my friend and colleague Jeff Chang has called a “cycle of crisis”? Crisis. Response. Exhaustion. Crisis. First I think we have to challenge our assumptions about who we are, to see how our stories are connected within political and economic structures that are screaming out for change.

THE WORLD IN WHICH WE LIVE

Over half a millennium ago, Christopher Columbus, financed by Spain, reached the Americas while trying to reach Asia in search of gold. On the island that is now the Dominican Republic and Haiti, he built the first European military base in the western hemisphere. He took indigenous Arawak people as prisoners, and killed those who refused to trade their bow and arrows. Two years later, the Treaty of Tordesillas, known as the Doctrine of Discovery, divided the world in half and claimed possession of the entire world west of that line for Spanish conquest, and all east of it to Portuguese conquest. The Portuguese were the first to begin the slave trade, trading in human beings from the west coast of Africa. Hundreds of years later Virginia’s slave codes would erect a permanent barrier to multiracial solidarity among enslaved Africans and indentured Europeans against the ruling class. Later, enslaved African people in Haiti would end French colonial rule in the largest slave rebellion in the western hemisphere.

I often narrate my own story by saying that I come from war. The reality is that since the Doctrine of Discovery, we have all come from war, with battles lines drawn by the global ruling class to preserve and expand their power.

Seeing ourselves as distinct, natural, and inevitable nations and racial groups has led to a kind of drawn out political and spiritual suicide, because these distinctions rely on and perpetuate violence. When Dr. King was questioned about why he was speaking out against the Vietnam War, he said:

At the heart of their concerns this query has often loomed large and loud: “Why are you speaking about the war, Dr. King?” “Why are you joining the voices of dissent?” “Peace and civil rights don’t mix,” they say. “Aren’t you hurting the cause of your people,” they ask? And when I hear them, though I often understand the source of their concern, I am nevertheless greatly saddened, for such questions mean that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.

We must understand how the world in which we live has shaped our relationships to each other. Our survival depends on our ability to think critically about our material conditions and our consciousness.

Just a year before Dr. King’s Beyond Vietnam speech, in 1966, the New York Times published William Peterson’s “Success Story: Japanese American Style” and the US News and World Report published “Success Story of One Minority Group in US,” praising Chinese Americans and Chinatowns. The model minority myth started to take hold of the American public imagination, though the seeds had been planted decades before. Chinese and Japanese Americans who previously had been seen as disease-ridden, untrustworthy, sexually deviant, and criminal were magically redeemed as exemplary non-whites. After WWII, U.S. elites needed to adjust America’s racial folklore to win the Cold War contest for global power. The Soviet Union criticized the United States for its racism, so the America created the model minority to prove the possibility of racial uplift while maintaining the validity of rules that justified the punishment of rebellious Blacks and other threats to the liberal capitalist state. This project was helped greatly by the 1965 immigration act, which selectively favored highly educated professional classes of Asian immigrants into the country while criminalizing migrants from Mexico and Latin America.

But this is also the same time as the fight to preserve the International Hotel in San Francisco’s Manilatown, when the owner, the Milton Meyer Company, threatened to demolish the building and evict its elderly low-income Asian residents. This was the same time as the My Lai massacre, when U.S. soldiers of Charlie Company of the 11th Infantry Brigade arrive at the village of My Lai. The unit meets no resistance from the 700 inhabitants, yet kills over 500 Vietnamese civilians including 119 children seven years old and younger. What did the model minority myth do for us, as Asians, by slicing and dicing our interests and our consciousness away from a global working class majority and toward a false exceptionalism?

As we well know, the war that Dr. King risked his life to denounce 50 years ago led to a refugee crisis. I was recently at a gathering of Grassroots Asians Rising, with 160 activists from Asian American and Pacific Islander community organizing projects around the country. There we heard Chhaya Choum speak, director of Mekong in the Bronx, who came to the US as a result of this refugee crisis. She described a conversation she had about Dr. King’s Beyond Vietnam speech with a lawyer who had worked with him at the time, who told her that King knew he would be killed because of that speech. She told us how surreal it was for her, a Cambodian refugee, to sit in that room, with that person, and talk about that speech. The cycle of crisis. She also told us that her community would soon be christening a new mental health clinic, fiscally sponsored by a Black health organization, to address the severe intergenerational trauma among Southeast Asian refugees. The name of the clinic? Beloved Community.

THE ENDURANCE OF THE COLOR LINE

In 1903 the great historian and civil rights leader W.E.B. Dubois prophetically stated: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” It is a well-known sentence that is rarely quoted completely. DuBois goes on to describe the color line as “the question of how far differences of race… will hereafter be made the basis of denying to over half the world the right of sharing to their utmost ability the opportunities and privileges of modern civilization.” In The Souls of Black Folk he says it is “the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea” and says, “It was a phase (emphasis mine) of this problem that caused the Civil War.”

DuBois was eerily prophetic. Today, eight men own as much as half the world population. We are now in another phase of the problem of the color line. The current crisis has multiple vectors including, quite simply, the survival of life on the planet. It’s a good time to take a global and historical view of the forces that have drawn and redrawn the color line, to dirty up the narrative of racism as simply individual hostility toward those who are different, and rather to see it as a structural problem.

Over the course of his life as a scholar and activist, DuBois came to understand the color line as a global system of exploitation, an evolving mechanism of human sorting that accompanied the development of western national economies and empires. The color line sorts the free from the un-free, the owners from the dispossessed, discerning who belongs and who does not belong within the nation-state or within humanity itself. Political theorist Cedric Robinson later called this racial capitalism, a general description of the West’s organization, expansion, and ideology of capitalist society as expressed through race, racial subjection, and racial differences – an ideology with its roots in European feudalism.

DuBois was an early forecaster of how the relationship between race, nation, and empire would drive major conflicts like anticolonial struggle and racial integration, and how it would inspire expansive freedom dreams. A consistent yet commonly overlooked mainstay of Black radical politics has been the demand not simply to be included in the nation, but to transform its very meaning by contesting capitalism and empire. That Reconstruction was left unfinished meant that this transformation never took place, and the rapacious logic of capitalism and western empire continued to brutalize Black bodies in ever evolving systems of exclusion and exploitation. This systematic devaluation of Black life, like the miner’s canary, portended growing ranks of the dispossessed that have crossed racial and national boundaries.

THE VIOLENCE OF BELONGING

The political utility of dominant American stories lies in their ability to shape how we see each other, and ourselves, as part of a shared national community. But to paraphrase historian Howard Zinn, nations have never been communities. American holidays, advertising, and textbooks make up a national mythology about multiculturalism that masks the realities of unresolved conflict. Historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz explains how the folklore of the “gift-giving Indian” giving corn, beans, log cabins, and more to the project of American democracy functions to normalize violence:

This idea of the gift-giving Indian helping to establish and enrich the development of the United States is an insidious smoke screen meant to obscure the fact that the very existence of the country is a result of the looting of an entire continent and its resources…

Settler colonialism, as an institution or system, requires violence or the threat of violence to attain its goals. People do not hand over their land, resources, children, and futures without a fight, and that fight is met with violence. In employing the force necessary to accomplish its expansionist goals, a colonizing regime institutionalizes violence.

An example from 1873 is typical, with General William T. Sherman writing, “We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children … during an assault, the soldiers can not pause to distinguish between male and female, or even discriminate as to age.”[1]

Exactly one hundred years after Dubois’s The Souls of Black Folk, Indian author and human rights activist Arundhati Roy published War Talk. In it she writes: “Nationalism of one kind or another was the cause of most of the genocide of the twentieth century. Flags are bits of colored cloth that governments use first to shrink-wrap people’s minds and then as ceremonial shrouds to bury the dead.”[2]

The violence of nationalism is built on the logic of belonging. The failures of capitalism and modern liberal democracy stem from their reliance on belonging as the basis for differential valuations of human life. Prison abolitionist and scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore puts this succinctly: “Capitalism requires inequality and racism enshrines it.”[3] Not everyone can be equal in value, so liberalism creates the folklore of race and nation to explain the borders between those who belong and the excluded/oppressed/dispossessed.

RACE AS RIVALRY

Like many of us, I have been grappling with language. For years, working in the racial justice movement, I have hit the wall on words and meaning. The following quote from critical race scholar Daniel M. HoSang, reflects my frustration when exploring the question of multiracial solidarity. It too often involves the reification of racial categories that gets in the way of forging new antiracist identities and shared political goals.

In queer studies, “queer” is not a population, but a verb, a political vision and an action – for example, queering a relationship, or to queer a critique. Also in disability studies, it’s not describing attributes of people, but challenging the idea of normalcy. Ethnic studies has been emptied of its politics… Who’s in a room? We count bodies, and then say it’s an indication of racism because there aren’t people of color. The argument is that there is a particular experience as people of color, but that’s not true… We also treat White as a natural category, not as an ideology, a way of looking at the world… We no longer have a vision of transformation. Instead, we believe that the distribution of harms by race is somehow a justice vision. Would it be just if people were distributed in prisons on an equitable basis? That’s the culmination of the racial justice project. We need to envision broader transformation.[4]

I’m no philosopher, but as a writer and former organizer, I know that language matters. Words like “felon” and “illegal” have profound material consequences. I have long been partial to Gilmore’s definition of racism as “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death,”[5] but have found that people often interpret this as reinforcing two false ideas: that racism only hurts people of color and benefits Whites, and that this, rather than the normalization of a differentiated humanity, is its greatest harm. I have tried experimenting with Saskia Sassen’s phrase “savage sorting” which describes the cruelly simple outcomes of complex chains of transactions in today’s global capitalism[6], but while it has a certain ring, it requires too much explaining. I have tested out my own language of “race as rivalry,” because what has been happening to the working class reminds me of Roman gladiator fights, or massive mixed martial arts cage fights. But in a culture that glorifies professional sports, this feels inadequate to capture racism’s inhumanity.

Assigning natural rights to some and not others is the folklore that drives bloodlust, rivalries over things that should not be at stake. The state-propagated idea of race and national origins as natural, as fixed categories of people who share innate essential qualities, is not only historically inaccurate; it is politically demobilizing. The reality is that we are “raced” in relationship to each other through a changing combination of rules, stories, accepted knowledge, and more. While these things may originate from those with power, we all participate in their perpetuation through day-to-day economic, social, and political action. Antiracist struggle requires not a reshuffling of categories but a replacement for the rivalries of capitalism, a new common sense and practice for how we live on this earth.

Examples of this abound in the experiences of global migrants. The US government relocated Southeast Asian refugees from the war that King denounced to urban sites of economic and political abandonment, where the War on Drugs was decimating Black communities. Refugee children of the 1980s grew up to encounter welfare and immigration laws in the 1990s that drove them into economic crisis, incarceration, and deportation in the 2000s. Longtime Cambodian American organizer Sarath Suong points out how his parents, displaced from the killing fields of Cambodia to a refugee camp in Thailand and then to a re-education camp in the Philippines, were groomed to be cheap labor by the time that they arrived in the United States. For Asian Americans, our entry into this nation, our arrival, has been as rivals. The biggest roadblock to multiracial solidarity is failing to recognize race as a system of state-brokered relationships within a global structure of deadly competition.

Sa-I-Gu was a lesson for Korean Americans in race as rivalry. What rivalries will the refugees of Syria face 25 years or 50 years from now? Which city blocks will they claim to own and defend? Which prisons will they end up in?

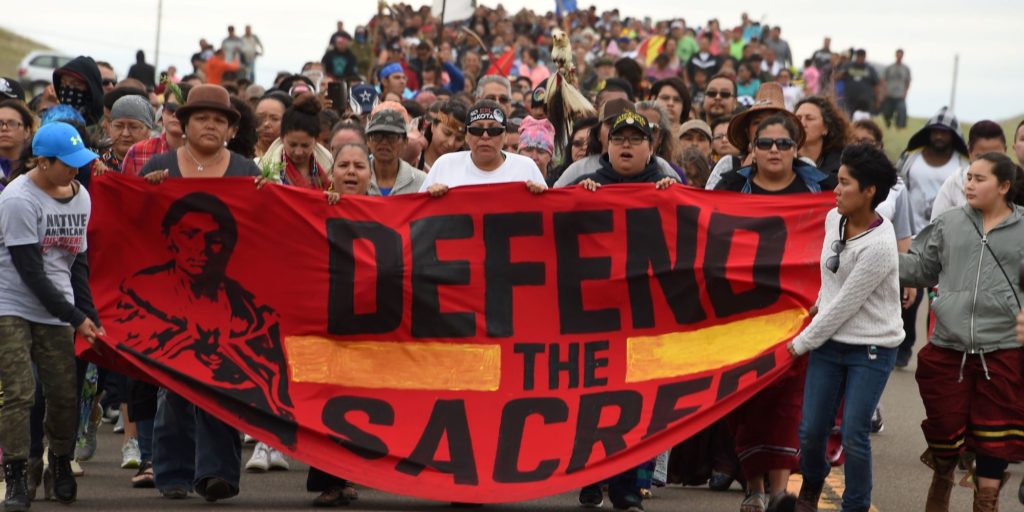

WHITE RAGE

Donald Trump’s administration has wasted no time spreading chaos, fear and confusion. Within days of taking office, the regime rolled out an anti-Muslim travel ban, suspended refugee admissions, green lighted construction of the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines, insulted America’s international allies, attacked the judiciary and the media, and conducted a raid on a Yemeni village that left nine children and 15 other civilians dead. While news outlets struggled to keep up with the torrent of White House gaffes and bombshells, Republican state legislators moved on numerous bills attacking unions, abortion rights, transgender rights, and public education; slashing taxes; rolling back regulations; criminalizing protest; and preemptively curbing the power of progressive cities to fight back.

Social justice movements have delivered on their own promise: to resist. The day after Trump’s inauguration a record-breaking 4 million people took to the streets in 600 U.S. towns and cities for a Women’s March that also inspired satellite marches around the world from Nairobi to Beirut to Tokyo. Just days later, thousands of protesters showed up at several U.S. airports to protest the detention of non-citizens from seven Muslim-majority nations that Trump attempted to exclude through an ill-fated travel ban. In communities across America, people who had never before participated in a march or rally stepped out of their comfort zones and into the streets. In this time of grave danger we must not forget, as my longtime friend and comrade Eric Ward so poignantly put it, that we are the storm, and we are here.

Meanwhile the wave of hate violence that swept the country immediately following Trump’s election has continued, most recently in Portland, Ore. Three men, Taliesin Myrddin Namkai-Meche, Rick Best, and Micah Fletcher, valiantly intervened as alleged white supremacist Jeremy Joseph Christian verbally attacked two young women, one who was wearing a hijab. Christian stabbed all three, killing Namkai-Meche and Best, and injuring Fletcher. Appearing in court, Christian shouted, “Death to the enemies of America. Leave this country if you hate our freedom. Death to Antifa! You call it terrorism, I call it patriotism! You hear me? Die.” The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that the number of organized hate groups has increased for the second year in a row. This year marks the 35th anniversary of the murder of Vincent Chin, mistaken as “a Jap” by white former autoworkers Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz. Christian’s actions reveal that the connections between race, nation, and white rage endure.

This volatile moment contains stark breaks from accepted norms. These include the executive branch’s aberrant behavior in the form of “alternative facts”, hostile press briefings, and rambling press conferences that lend credence to the refrain, “This is not normal”. But they can also be seen in a mainstream media that has found itself under attack, with some journalists and editorial boards adopting insurgent positions. Media professionals are talking about their civic duty, reclaiming the banner of investigative journalism in service to democracy and not to market shares. Just weeks after the election Marty Baron, Executive Editor of The Washington Post, said to his colleagues that “holding the most powerful to account is what we are supposed to do. If we do not do that, then what exactly is the purpose of journalism?”

Career civil servants from the State Department to the Environmental Protection Agency to NASA are actively dissenting, whether through leaks or rogue Twitter accounts. Former staffers from the Obama administration have emerged as sources of advice and insight into political resistance, through podcasts such as Pod Save America and projects like Indivisible. Democrats in cities and states have openly defied the Trump administration by declaring themselves sanctuary governments and launching lawsuits against Trump’s policies. Corporate giants like Starbucks, Microsoft, AirBnB, Amazon, and others have spoken out against Trump’s policies and adopted various forms of dissent, as have numerous celebrities.

Resistance has gone vogue.

These are positive signs, but resistance to rightwing authoritarianism must do more than settle back into the norms of liberalism. The current crisis demands much more than a reversion to the neoliberal status quo. Neoliberalism created this crisis. It is represented most recently by the Obama administration but originates in a ruling class backlash against the Keynsian economic policies of the middle of the last century. It has led to a weakened labor movement, unprecedented inequality, resegregation, hollowed out economies both in former industrial manufacturing cities and in rural counties, a mass incarceration crisis, a mortgage crisis, widespread precarity, and unending war. It pumped the color line with steroids while signaling multiculturalism as a virtue by presumed national consensus.

The effect was a perception among precarious or dispossessed Whites that racial justice meant multiculturalism, and that meant yoga studios, MacBooks, lattes, high tech jobs, and other urban privileges that are out of reach for most White people. Leaders of racial justice movements saw the Kool-Aid for what it was, and felt ever-growing frustration at the appearance of diversity with not only a lack of justice but active brutality in the form of gentrification, criminalization and police abuse, skyrocketing mass incarceration, and continued divestment from public services and infrastructure. Unfortunately, the demands of the racial justice movement were not easily discernible from the cultural consensus put forth by the neoliberal class, particularly following the election of Barack Obama, even though they were oceans apart. Longtime organizer N’Tanya Lee puts it this way:

The destruction of the Black left means that liberal folks are in charge of saying what liberation is for Black people. They get to be part of defining civil rights and racial justice in ways that have nothing to do with Black people’s interests, really.[7]

Now here we are.

Like Black and Brown rebellions from slave revolts to coolie mutinies to today’s Standing Rock, what is happening in American politics now is a form of rejecting dispossession. The suffering and precarity underlying Trumpian white rage is the result of racial capitalism. The difference is that the Trumpian whitelash rejects dispossession not to expand the possibilities of life, dignity, and self-determination for all, but to reanimate an earlier phase of the color line, an exclusive definition of the nation that hordes life exclusively for its white citizenry.

RACE CONSCIOUSNESS

Implicit bias has become a popular topic for racial justice advocates, and rightfully so. However, while social cognition research may capture our brains as they are, this is the result of the world around us. Segregation and implicit bias are mutually reinforcing. Markets by definition require discrimination, because they rely on rivalry. When that is the central operating logic of the economy, when your physical survival relies on your competitive ability to produce profit for the ruling class, then the human brain’s propensity to categorize people racially is, in fact, about survival. This is the logic we must change.

The development of chattel slavery necessarily included norms of religion, gender, sexuality, family formation, ability, etc. Intersectionality is important because it is the key to unlocking the capitalist state’s social control. Surviving the modern world has not demanded much of us in the way of universal empathy. In fact, it has increasingly required us to consent to the inevitability of someone else’s dehumanization or absolute elimination. Continuing to see ourselves as distinct groups independent of one another blinds us to the workings of the larger system, and to solutions. One place to start may be to revisit those movements that have always had an expansive vision of such transformation.

In a speech published in 1984, Black feminist, lesbian, author and activist Barbara Smith said: “We are in a huge mishmash created by mad people at the top, and we are constantly trying to rectify the situation. I see the process of rectification as what Black feminism is all about: making a place on this globe that is fit for human life.”[8]

Speaking to SNCC in 1964, Ella Baker said: “Even if segregation is gone, we will still need to be free; we will still have to see that everyone has a job. Even if we can all vote, but if people are still hungry, we will not be free… Remember, we are not fighting for the freedom of the Negro alone, but for the freedom of the human spirit, a larger freedom that encompasses all mankind.”[9]

Contrast this to the following statement by U.S. Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina in 1849: “The two great divisions of society are not the rich and the poor, but white and black, and all the former, the poor as well as the rich, belong to the upper class, and are respected and treated as equals, if honest and industrious; and hence have a position and pride of character of which neither poverty nor misfortune can deprive them.” This reflects the impacts of the color line, of racial capitalism, and of modern liberal society on our material conditions and on our consciousness.

UNDOING VIOLENT CO-ANNIHILATION

Black subjugation, settler colonialism, and war diminish the universal meaning of life itself. Oppressed groups have fought to penetrate the wall dividing the free from the un-free, the normal from the aberrant, the world of the living from the world of the dispossessed, to make America’s declarations of equality less untrue. But the wall endures, the color line across which race does its “savage sorting”. On one side of that line, the world of the living is populated by the creative class, the winners, the gentrifiers, the political descendants of yesterday’s colonial settlers. Today’s prison industrialists are descendants of yesterdays’ eugenicists, today’s national border policies offspring of yesterdays’ redlining.

In this world of the living thrives the real identity politics that brought down the Democratic Party in the 2016 election: the urban neoliberal, the progressive who is just fine in his skin, benefiting from the dislocation, dispossession, or death of another as long as there is a net profit on the balance sheet of progress — measured by Gross Domestic Product, average life expectancy, unemployment rates, and other data points. The logic, structures, institutions, and policies that produce this identity are the “giant triplets” that Dr. King predicted would lead to “violent co-annihilation” – racism, war, and capitalism. These are the invisible sharp edges of power sorting the world of the living from the dispossessed, violently dislodging us from the earth and one another such that phrases like “Black lives matter” and “Water is life” become necessary.

In this context, culture has fallen into the grab bag of markets. The ruling class artfully takes the trinkets of various subcultures to fashion a super-culture of the global marketplace: western democracy anchored by America, intercultural, interconnected, idealistic, international, innovative, intelligent… So many I’s that make up an us formed against them. The west took “bits of colored cloth”, fashioned a transnational flag, and expected all rational people to pledge allegiance to it, to the winners of globalization, to free markets, to tanks/guns/drones, to progress, to common sense.

I believe that the transformative potential we need lies in the growing global ranks of the disposessed, who are not all experiencing the same things, but who are prey to the outcomes of a callous economic system that so few of us understand. This is where a new kind of human identity can emerge, not from an invitation to join the winners, not at the doorstep of the living. It will emerge from the knowledge among the dispossessed that I am not you and you are not me, and that this is only a problem if our differences result in consequentially different life outcomes, if they determine the ability of one of us to eat, to live free of violence, to have adequate shelter, to form intimate human relationships, to be healthy, to imagine and create. The truth is that we need one another to do these things. We have underestimated the carnage of the modern world, and it is time to put ourselves together, perhaps for the first time.

My friend Hannah Jones is a volunteer with Chaplains on the Harbor in Grays Harbor County, Washington, a former timber-dependent county on Quinault Indian territory. She sent me an email on International Women’s Day that moved me deeply. I read it several times.

We saw the stretch of rail yard along the river where many homeless people set up camp, but are routinely harassed by police or have their homes destroyed by sweeps. We saw the hospital where one young man was turned away because he was profiled as “drug seeking”, only to die at the third hospital he tried in Olympia. We heard how Child Protective Services has been charged with a lawsuit for trafficking children they take away from mothers in poverty. We saw the spot where a young man, being chased by cops, jumped into the river and drowned. He was not the first and he won’t be the last. We threw flowers into the river at that spot, one by one, to honor and remember all of the people from the Grays Harbor community who have been killed by the violence of poverty. It’s a clear view into how the state and the wealthy manage people who are considered useless. When they have no buying power to be consumers, and when their labor isn’t needed.

And through this mess, people are surviving, resisting, and creating. There’s a self-governing tent city held together by Larry, a former logger who was injured on the job years back. He talked with me about his conversations with men in the camp about their treatment of women in the homeless community. Emily, a budding organizer with Revival Grays Harbor, almost single-handedly runs a cold weather homeless shelter during the winter with her spare time. She knows everyone in town and hustles blankets, peanut butter, and anything else that could keep people alive. Most of the shelter volunteers are homeless themselves. Emily’s love for her people and home is palpable, seemingly boundless, and fierce as hell. Reverend Sarah with Chaplains visits people in jail, delivers letters for them, gives sandwiches away under the bridge to members of the homeless community, holds people through immense pain, mourns the dead, shows up for people when no one else will. Scott, Larry’s friend in tent city, looks out for Larry and makes sure he exercises his bad hip. Idalin, visiting from Oakland, talked with people from tent city about the commonalities between her struggle as a poor woman of color and theirs out on the Harbor. Another woman from the New Poor People’s Campaign, Shailly, brought her 6-month-old with her from New York. He took everything in with wide eyes. We all ate together – people cracked jokes about baptists, reminisced about LA in the 60’s, swapped war stories, played with the baby, shared sage advice about the dangers of cops.

…I’m feeling deep down how profoundly feminist the work here is. It’s not a shallow feminism. It’s not watered down. It’s not merely lip service to it (the word wasn’t uttered today because sometimes when it’s practiced, it doesn’t need to be spoken). It’s a deep commitment to each other, to care of a community, to a world beyond the narrow confines of work as a job, to connection despite stories that try to divide and alienate us, to the conviction that no person is expendable, to liberation, to holding people at their messiest, to fighting for a vision beyond mere survival. To playing with babies and cooking and eating and crying and planning and living.

It is time to say everything we know. We need a way of relating one life to another life that we can see, smell, taste, and touch; a politics that embraces every one of us, that nourishes both sensuality and intellect, that rewards our curiosity about ourselves and one another, and that allows us to reimagine and practice what being with one another means. Liberalism, capitalism, and modernity are crumbling. In this time of rupture and fear and uncertainty, we should resist the impulse to put ground under our feet by reaching for the easy and familiar modern liberal fixes. As the saying goes, it doesn’t get easier; we get stronger. What are the human capacities we need, the spiritual muscles we must exercise to be more curious about one another and together build a new society?

[1] Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (ReVisioning American History). Beacon Press, 2015. Print.

[2] Roy, Arundhati. War Talk. Cambridge, Mass: South End Press, 2003. Print.

[3] Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. “The Worrying State Of The Anti-Prison Movement | Social Justice”. Socialjusticejournal.org. Feb. 23, 2015.

[4] ChangeLab National Strategy Summit. Seattle, WA. April 20, 2013.

[5] Gilmore, Ruth Wilson. Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, And Opposition In Globalizing California. 1st ed. University of California Press, 2007. Print.

[6] Sassen, Saskia. Expulsions: Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap of Harvard U, 2014. Print.

[7] ChangeLab National Strategy Summit. Seattle, WA. April 20, 2013.

[8] Alethia Jones and Virginia Eubanks, eds., with Barbara Smith. Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around: Forty Years of Movement Building with Barbara Smith. State University of New York, 2014.

[9] Zinn, Howard. You Can’t Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times. 1st ed. Beacon, 2017. Print.

2 replies on “Hearts open, fists up: the color line”

Thank you! This is so meaningful to me today.

Great article!